TO TAKE A BACKWARD LOOK

These are the days when Birds come back —

A very few — a Bird or two —

To take a backward look.

HOPE is indeed a thing with feathers. In a landscape entombed in cement, the sight of a wild bird soaring — circling over the freeway, alighting on the towers of high-tension power liness — offers a sudden thrill.

If it’s a majestic bird, it’s probably a hawk.

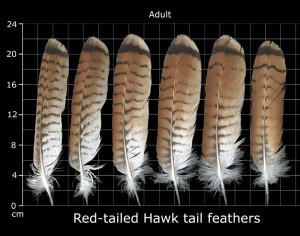

In urban Southern California the two most common are the litheCooper’s hawk (Accipiter cooperii), which lurks in yard trees and jets out to nab little birds, and the larger red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis). The latter is the one you see coasting around in lazy circles, buoyed by upwelling currents of hot air called thermals.

Wanting to know more about these birds, I called conservation biologist Dan Cooper, the consultant behind Cooper Ecological. Cooper has been observing LA birds since he was a teen. He’d know where to find a red-tail.

He took me to the Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery, which dates back to the 1880s. As we strolled among century-old gravestones and towering pines, Cooper pointed out that the West Adams area is one of the most densely populated parts of the city. “This cemetery is one of the few big green patches. Any one who’s been down here knows it’s solid urbanization.”

It’s not a place you’d expect to see a lot of wildlife, I said.

“There’s not a lot here,” he agreed, “but a few things that have adapted and we just saw one, the western bluebird. The common birds here are going to be house finch, mourning dove, and [European] starling.”

But as we drove in, Cooper had spotted a red-tailed hawk perched atop one of the pines. So, binoculars in hand, we went looking for it.

“They like tall trees to place their nest,” said Cooper. “And they’ll often roost in tall trees, sitting right at the top. But when they hunt, they hunt by circling and soaring around, diving down on things; they’re not sit and wait predators.”

How do they hunt?

“The adults will circle,” explained Cooper. “When they see something, they nose dive. Just before they hit the ground, they’ll pull up, stick out their feet and land on their prey and squish it on the ground, and kill it with one hit–they land on it with their talons extended. After they land, they’ll fan their wings out a bit, take off to a perch with the prey in their feet and start pulling it apart with their beak.”

In addition to favoring cemeteries and other places where tall trees skirt open areas, red-tail hawks also seek out trees rooted on hillsides or even slight rises like the one the Rosedale Cemetery blankets. “You think of LA as being flat,” said Cooper, “but there are actually these old ridges and little hills all through the city. And birds still do select for this topography. In the depressions, where you have a lot of sycamore trees, you’ll see riparian species, like red-shouldered hawk, are still there.”

In addition to favoring cemeteries and other places where tall trees skirt open areas, red-tail hawks also seek out trees rooted on hillsides or even slight rises like the one the Rosedale Cemetery blankets. “You think of LA as being flat,” said Cooper, “but there are actually these old ridges and little hills all through the city. And birds still do select for this topography. In the depressions, where you have a lot of sycamore trees, you’ll see riparian species, like red-shouldered hawk, are still there.”

Cooper can identify birds flitting by so fast that most people barely see them. He pointed out darting swallows and a black phoebe perched on a headstone (a stand-in for the boulders the bird evolved with). But the hawk was eluding us.

Red-tailed hawks are native to the LA basin. Some are resident; others drop in for the winter. Before the ranch era, nesting and roosting trees were far less common in the area. “The hawks may have nested in sycamores where Echo Park Lake is or MacArthur Park is,” said Cooper, “then foraged here on the plain.” As people planted eucalyptus and other large trees, the hawks moved in.

As human development proliferated, so did introduced species such as theeastern fox squirrel, rock doves–a.k.a pigeons—and possums. “We’ve have garbage all over the city, squirrels eat our garbage,” said Cooper, “So we have this inflated prey base. If every one fed their cats inside, we wouldn’t have possums, squirrels, and rats everywhere. We’d have a lot lower population of prey for hawks.”

An echoing “CHEEeeev” pierced the sky above us. A brown bird with broad wings spanning four feet glided past, its rust-colored tail fanned. “That’s a red-tailed hawk,” said Cooper. The bird circled, cutting in front of a distant airplane, then disappeared behind a tree.

A few minutes later the hawk was back in view—with a mate. It folded its wings into its body and plummeted, headfirst. Then the bird pulled up—as if that death dive was just a joke–and joined the other hawk. The two zigzagged in unison, yellow legs dangling, giving the impression of a pair of hang gliders.

“That’s their courtship,” said Cooper.

“What’s the deal with the dangling legs?” I asked.

“It means I like you,” Cooper guessed. “I like your style.”

It was spring, the birds were courting, so we searched for a nest. No luck.

A couple days later, I met Cooper on a suburban road in La Habra Heights. A large bowl of sticks was nestled in a two-story eucalyptus. Squinting into some binoculars I saw two motley young hawks—downy heads and partially feathered bodies—preening their newly sprouted wing feathers. (A sibling lay in the nest.)

One of the juveniles tottered to the nest’s edge, gingerly unfurled its wings, and looked down.

Cooper told me that a red-tail’s first flight is really a hazardous jump. “They’ll sort of flop to the ground,” he said. “At that point really vulnerable to being eaten by cats and coyotes, or just killed in the fall. But they do have a little foliage between them and the ground so they may hit the crown of one of these [native] walnut trees.” The fledglings will flap and crash around nearby trees until they learn to fly.

The young hawk apparently thought the better of it and stepped back from the edge. A good decision considering its parents soon returned. The big babies plead for food with a breathy calls sounding something like pweese, pweese, pweese!

As the female—the bigger of the two adults—wheeled around the nest, Cooper told me, once the young birds fledged, they would leave the area. “They might stay a few weeks, but eventually they’ll disperse,” he said, “find their own mate, and set up shop somewhere else–maybe in the Puente Hills, maybe somewhere far away. It’s pretty amazing where these birds will make a home.”

This web story first appeared on Chance of Rain. Thanks to editor Emily Green.

Click here for an earlier audio version from KPCC's Off-Ramp.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Please share your thoughts